REVIEWS / MENTIONS

Young Ponderosa Pine, 2022, archival pigment print

Orange Lichen, 2022, archival pigment print

J. John Priola @ Anglim/Trimble JANUARY 17, 2023

by Mark Van Proyen

The history of photography has always been beset with a kind of schizophrenia. On one hand, it is a chronicle of technological developments moving in the direction of informational precision, while on the other, it is a history of poetic vision. Sometimes, both histories combine in an artist’s work. Rarer still are the moments when an artist purposefully plays each against the other to capture and the hidden dialog between them. John Priola’s exhibition of ten recent photographic prints, Natural Light/ Symbiosis, slyly exemplifies such moments, eliciting slow and careful looking.

This exhibition of archival pigment prints (all 2022) derives from high-resolution digital files, only slightly embellished by image editing software. They divide into three thematic groupings. One features clusters of leafless trees set against almost white backgrounds intimating a burst of early afternoon illumination, captured from an upward-looking angle, making the trees loom tall in relation to the viewer’s cone of vision. Perched high in the barren tree branches are clusters of symbiotic foliage indicated by the works’ titles to be mistletoe, appearing as nests fashioned by highly motivated arboreal critters. In Mistletoe, for example we see knots of teeming foliage crawling up into the branches of a barren tree, looking like an obese python covered in perfervid vegetation. Sebastopol Mistletoe, a diptych, features several bare trees hosting several smaller examples of such clusters, while the largest work in the exhibition, Windsor Mistletoe, is an interconnected trio of similarly themed images.

Priola’s recent images are not particularly large by the standards of contemporary photography, nor are they preciously small. They shy away from flamboyance, their crystalline hyper-focus evoking the brittle dissections of Karl Blossfeldt’s nature studies from the late 1880s to the early 1930s. To look closely at these images is to marvel at the subtle, albeit overwhelming, level of informational detail they reveal about the surfaces described therein, making them comparable to the work of f64 photographers such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. Priola’s images go so far in the direction of “straight photography” that they become surreal by default, echoing a statement made by Susan Sontag saying that Surrealist photography was redundant because photography was already intrinsically surreal before anyone tried to label it as such.

Each image places the viewer in the same uncertain position of the photographer/protagonist of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow Up, who discovers that the closer he examines a photograph of a murder scene, the less sure he is about what he sees in it. This attribute of dissolving certitude plays out in a quartet of images featuring grey pine tree trunks frontally illuminated against inky black backgrounds, intimating a cold winter night. Each is centrally located in a 26 x 20-inch picture space, unadorned by branches but still rich in the visible detail of the surfaces revealed to the camera’s gaze. In fact, Priola’s pictures reveal so much detail that some viewers might start seeing things that are not there, like areas of phosphorescent nematodes enlivening the desiccated surfaces of the trees. Therein lies the underlying drama of Priola’s new photographs: They reveal the sharp and subtle juxtaposition of dormant and living forms, echoing the split history of photography understood as one of technically codified verisimilitude and another of elegiac evocation.

Still-life works represent another subgroup in this exhibition, these literalizing the Latin idea of Nature Mort. Orange Lichen gets its name from the color of the flat background upon which we see a sprig of lichen presented like a biological specimen. It does not seem to be fully alive, nor does it seem to be fully and finally dead. It seems frozen between those states, its vitality yet to be stolen by the passage of time or the camera’s scrutiny. Such scrutiny implicates the beholder as an impassive witness who helplessly stands back because there is nothing else to do other than savor the passing moment.

John Priola: “Natural Light/ Symbiosis” @ Anglim/Trimble Gallery through February 25, 2023.

About the author: Mark Van Proyen’s visual work and written commentaries emphasize the tragic consequences of blind faith in economies of narcissistic reward. Since 2003, he has been a corresponding editor for Art in America. His recent publications include: Facing Innocence: The Art of Gottfried Helnwein (2011) and Cirian Logic and the Painting of Preconstruction (2010). To learn more about Mark Van Proyen, read Alex Mak’s interview on Broke-Ass Stuart’s website.

San Francisco Examiner - Visual Arts January gallery guide

By Max Blue | Special to The Examiner Jan 6, 2023

J. John Priola: ‘Natural Light/Symbiosis’

The human brain can’t process the visual complexity of every leaf on a tree; instead, we fill in what we assume is there. J. John Priola’s photographs force our brains to work a little harder. His solo exhibition, “Natural Light/Symbiosis,” at Anglim/Trimble — coinciding with the publication of his monograph “Natural Light” (Kehrer Verlag) — presents pictures of verdant trees, singed trunks and mossy branches, in all their detail. Priola’s photographs are dense the way that nature is dense — in part because they are of nature, but also because his compositions feel like microscopic examinations of multitudes. Visual clutter rarely produces such tranquility as it does here. Anglim/Trimble Gallery, 1275 Minnesota St., S.F. Free. anglimtrimble.com

CULTURE | NOVEMBER 8, 2022 6:09 AM

“Natural Light” Is the Captivating New Monograph by Contemporary Visual Artist J. John Priola

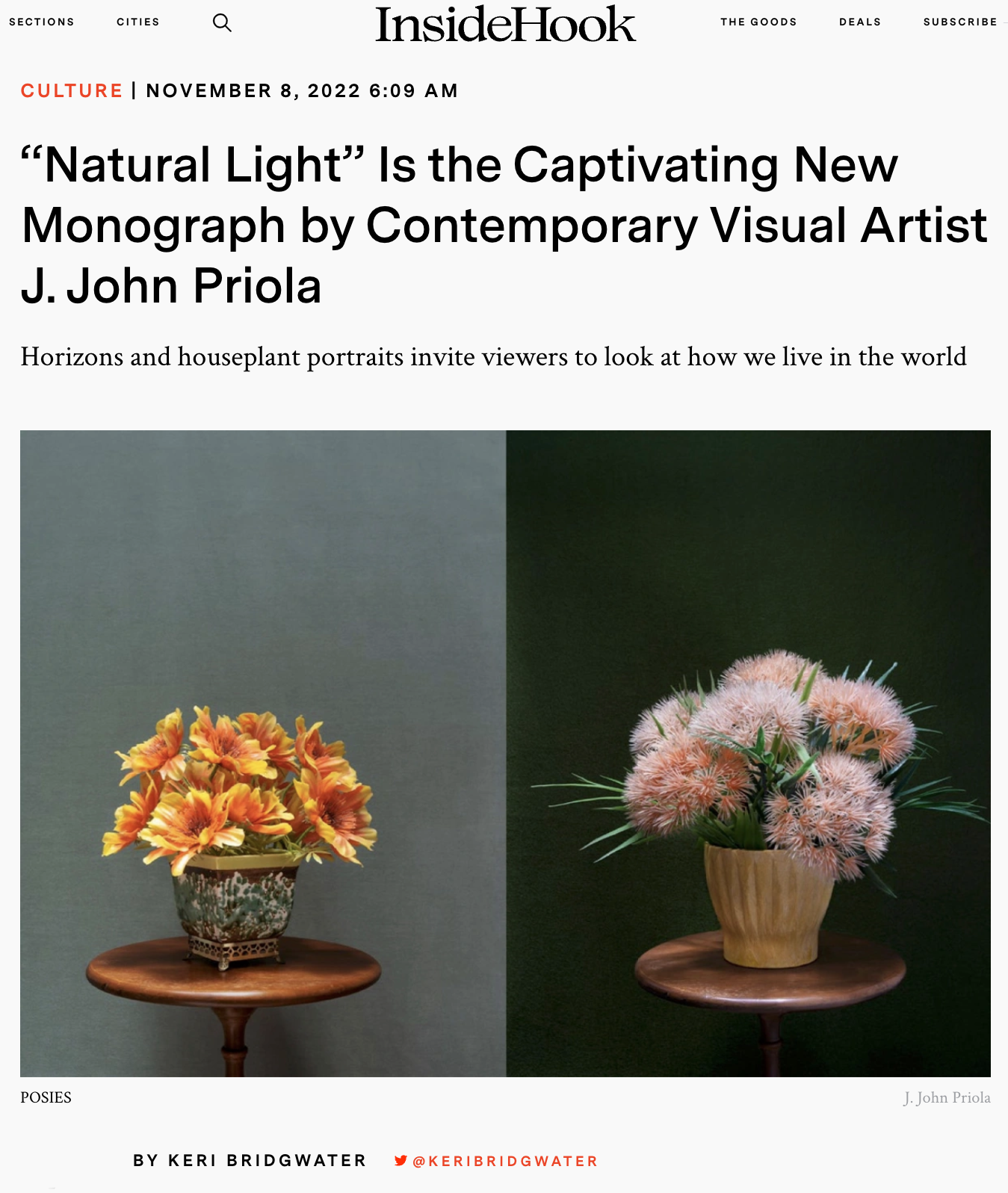

Horizons and houseplant portraits invite viewers to look at how we live in the world

BY KERI BRIDGWATER @KERIBRIDGWATER

Pretty posies, foliage arranged seemingly just so around a black void and pink Belladonna sprouting in a barren side yard. At first glance, the photos in J. John Priola’s new book are perhaps simply snapshots of ikebana-like arrangements and Google Street View-style captures of plants surviving against the odds in sometimes rather stark urban settings. Much like the centuries-old Japanese art of flower arranging, his images are spare but deliberate in their construction.

They offer an invitation, Priola says, for people to look a little longer.

“I’m a visual artist, and composition, like beauty, is my friend,” he says. “ I love all that, but this stuff is not on the surface, and I don’t make it easy. I like the distance photography supplies as it allows more of an unfolding to understand a picture. It seeps in slowly.” In the book, selects from his GROW: Houseplant Portraits series illustrate an abstracted form of storytelling. “If someone looks long enough or it begins to resonate, they’ll start to think about the owner or the caregiver more than the actual plant. The image becomes the vehicle to the meaning itself,” he explains.

The idea for Natural Light percolated for several years, but the pandemic allowed Priola to finally bring it to life. Featuring work from 12 different series made over 20 years that “investigates the natural and unnatural world,” each section is prefaced with a photograph taken by his mother. Growing up on a farm in Colorado, Priola didn’t appreciate those bucolic formative years until he was older. Summers coincided with growing season and months of hard work, but he always gravitated toward plants (during high school, he turned a spare room into an ad hoc greenhouse) and later photography, thanks to Mrs. Priola, who always had a camera out.

“I used her SX-70 Polaroid to start with, and the pictures would appear in front of my eyes. It was motivating,” he says. A woman ahead of her time, Carol Priola cultivated blue spruce and ash maple saplings to sell when the farm struggled.“She never studied to become a horticulturist but was the kind of woman who, had she been born in a different era, would have been an entrepreneur,” Priola explains. “She raised beautiful landscape trees and sold them when they matured and put all of her kids through college with the proceeds.” Priola says the book is a tribute to her photographs. It also features some of the trees that she grew. In the section titled “Tree Labels,” several images are included of saplings long-since grown bought by the care facility where she spent her final days. Full circle. As Priola puts it, “Two generations of people who have harnessed their awe of nature.”

Despite having his work in permanent collections of major museums like the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and The Metropolitan Museum New York, and 25-year tenure as a senior lecturer in the photography department at the San Francisco Art Institute, Priola doesn’t like the label “photographer.” “It’s limiting because there are preconceived notions about what it means,” he says. The term “shoot” versus “take” is also important. “Shooting has a different connotation than taking. It’s the difference between a photographer and an artist. I like taking pictures,” he clarifies.

Since graduating with an MFA in 1987, Priola has seen a seismic shift in the medium of visual arts and photography and says the latter has become increasingly ubiquitous. These days, anybody can take a good picture. A “hardcore film person,” he went into the digital world “kicking and screaming” but has now fully embraced it — even finding a home for long-running project Plant Sightings on Instagram. While Priola takes photos of houseplants and windows on his walks with a smartphone, he uses a medium-format digital camera for everything else. “The other work I do is more intentional. More thought out and not by happenstance,” he says.

Much like vinyl has enjoyed a recent renaissance, Priola believes analog also has its place in art — it’s just a different way of capturing light. Even the print emanates differently. “With digital, ink is on the surface of the paper, but with analog, it’s in the surface. I still make gelatin silver prints, but not as much,” he says. When I ask if the immediacy of digital takes him back to the instant satisfying fix of Polaroids from his early photo-taking days, he laughs and says it’s not that deep.

“Both mediums are difficult, challenging and exciting,” he answers. “It’s like the difference between an oil and acrylic painting, just a different process.” On the subject of “process,” as our chat concludes, I ask how he feels his work has evolved over a nearly four-decade career. “Grasping tighter and tighter to metaphor,” he tells me. “Because all those things, all those pictures, whether they’re a tree in the world or a flower, they’re all real people. They all stand for something.”

Priola has a whirlwind few months ahead. First, he’ll attend the international photography fair Paris Photo, concluding with a book signing on Nov. 11. Then, it’s back to San Francisco for the launch of Natural Light at Saint Joseph’s Art Society on Nov. 16 with readings by Rita Bullwinkel and Claire Daigle, who both wrote essays for the book. He shares that a portion of proceeds are being donated to non-profit City of Dreams. “An amazing organization that works its butt off and runs these really cool gardening programs for kids around Bay View,” he notes.

In January, his latest solo show — which centers on his monograph but will also feature new work — opens at the Anglim/Trimble Gallery and runs through the end of February.

THIS IS THE BEST WAY TO START COLLECTING LOCAL ART IN SAN FRANCISCO

The Svane Family Foundation's Ark Project commissioned works from 100 artists that are now up for auction

BY DIANE ROMMEL

San Francisco has a well–documented problem: cities structured around the needs of the young and wealthy are rarely also the same places that respond well to the needs of its creative class — the people waiting or bartending or yoga-teaching part-time to allow them to dedicate their full-time selves to their art. So that creative class decamps: for cheaper rents and easier lives, in Los Angeles, Brooklyn, Berlin, Stockton. For the artists, gallerists and art-loving humans left behind, this is a calamity. Happily, some innovative thinking is being deployed to halt that wave mid-crest here in S.F.: the Svane Family Foundation’s ongoing Ark project.

The set-up is intriguing: instead of writing a check to a local arts-boosting organization, Svane commissioned 100 S.F. artists to produce work, with $10,000 behind each project. Those pieces are now up for auction, through September 30 — giving those artists exceptional visibility to the city’s collector class. All the proceeds raised will go to ArtSpan, the organization run by Joen Madonna and doing all it can to keep artists here. As circles go, it’s laudably virtuous. And with bids — at press time — as low as $600, there’s something for most buyers here.

“The Ark program was designed first and foremost to get money to artists directly, as quickly as possible, at a time when the majority of artists were really suffering from the closures and postponements of the pandemic,” says SFF executive director Amie Spitler. “Once we had those funds to artists, it evolved into a way that the 100 works commissioned could be used to rev the engine of the entire arts ecosystem — this is the ‘giving loop’ model we’re operating from, where our initial investment can be paid forward into the greater art community that sustains artists long term. We’re trying to show how all of this is connected, and where there are different opportunities to get institutions and individuals involved in supporting the artists that we all benefit from having in the community.”

Among those 100 works are a Barry McGee, a glorious Linda Connor and a striking Aaron de la Cruz that will undoubtedly appear soon on an episode of Billions, in one of the smarter venture capitalist’s home offices. There’s also J. John Priola’s gorgeous photograph of a bouquet — titled “Bouquet” — featuring hand-crafted flowers made by 20 different San Francisco cultural organizations and nonprofits, a gorgeous representation of the city itself.

Priola says he understands the need for innovative action. “It’s tough, and it’s getting tougher,” he says of building a career within the S.F. art scene. “When I first came here, there were so many opportunities for artists to show their work — to get a one-person show, to get a review in the paper, to get eyes on you and your work. It’s increasingly impossible for emerging artists in the city now, because so many of the galleries have left. But even now, I’m seeing little galleries born out of necessity, and I am gratified to know that there are still people in San Francisco who recognize the necessity of art here.”

For Madonna, the influx of cash raised by the auction will help cover operational costs as well as complete the financing of the organization’s new “future home,” the Onondaga Art Center in the Excelsior, which will include artist studios, a community meeting space, a classroom, a resource center and a collaborative art gallery. “This was a great way to infuse a million dollars into the art ecosystem in San Francisco,” she says. “Those 100 artists were able to be inspired and make work. Helping people make work is so important — I think back to the WPA era, and how important government action was there. And then instead of that work being a static piece of art, it comes back in this auction format, so people get to see the entire collection, and be inspired by the theme of the Ark. And then the proceeds of that come to us, but we get to reinvest and reinfuse that money back into the art community more broadly, including creating an art center that will last for generations. It’s the gift that literally keeps on giving.”

Like we said: a virtuous circle, benefiting the city, its artists and let’s not forget its collectors, who now have the opportunity to bid on 100 pieces of work by many of the city’s best artists.

JUXTAPOZ Art & Culture

September 10, 2021 | In Session

“Experiences and programs that connect us to one another help everyone be better neighbors. We grow more as a community when we understand, listen and show up for one another.” Those words could have been gently admonished by Mr. Rogers, who was referring to neighborhoods everywhere, but no, they’re clear, simple wisdom from Zendesk founder and CEO Mikkel Svane, who has demonstrated a great habit of encouraging volunteerism among his employees. And apparently, he shows up too. The Svane Family Foundation was established in 2019 to support local artists and cultural institutions, who rightly depend on patronage, but were doubly undermined as a result of the pandemic. Along comes Svane, who’s offering a modern day Ark to help navigate the choppy waters.

His foundation has given a $10,000 commission to 100 artists, whose work will be exhibited September 7 through 27, 2021, at the San Francisco Art Institute and auctioned on Artsy with profits benefiting the non-profit ArtSpan, which provides Bay Artists with practical “post-grad” opportunities and skills, such as professional development and artist networking mixers, as well as youth open studios and community events that acquaint and enrich folks of every stripe. As the oldest art school west of the Mississippi, SFAI is a beautiful and symbolic host for the auction. Founded by a group of artists, writers and neighborhood leaders, its roof terrace overlooks the City, celebrating the panoramic openness of the liberal arts. Fully grasping the importance of education, The Svane Family Foundation asks the question, “What do you want to carry into the future?”

Among artists like Barry McGee, Alicia McCarthy, Dana King and HP Mendoza, J. John Priola presents the archival pigment he calls Bouquet, which is such a pure interpretation of this ongoing mission. A graduate of SFAI, Priolo describes, “In manifesting and realizing Bouquet, I asked over 49 organizations, institutions and individuals to make flowers that represented their cultures and communities.” The Bayview Opera House, The Women’s Building, Asian-Pacific Islander Culture Coalition and Irish Cultural Center are among the spectrum, “This bouquet holds so much more than metaphors and symbols; it holds love, hope, the creative zeitgeist of identifying, making, craft and beauty. I was able to collaborate with so many extraordinary, wonderful, lovely human beings. This is my contribution.”

“We need the vibrant joy and raw expression artists bring to our lives”, urges Mikkel Svane, whose efforts demonstrate that art education has no physical, generational or intellectual boundaries. —Gwynned Vitello

For more information, go to www.svaneff.org

GLEN PARK ASSOCIATION

FEBRUARY 22, 2019

Murray Schneider

J. John Priola, who lives on Surrey Street only blocks from Glen Canyon Park, was born on a five-acre farm in Colorado where his parents put up field corn for silage and grew sweet corn for more than just their Thanksgiving table.

“My mother sold the corn from a stand,” Priola told the Glen Park News, “but she also cultivated a tree farm. She’d buy blue spruce and ash maple seedlings, plant and prune each and then sell them to landscaper designers.”

Priola spoke soon after a February 7 opening of his Dogpatch show Natural Light,his new photography exhibit mounted at Anglim Gilbert Gallery at 1275 Minnesota Street.

Natural Light remains at Anglim Gilbert through March 9.

read complete article here

SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

JANUARY 9, 2015

Kenneth Baker

California photographer J. John Priola works on the threshold of conceptual art.

In earlier work, he took nighttime shots of illuminated house numbers, bringing out their creepily uninviting quality and somehow making them look like possible markers of fate.

In new work at Anglim, Priola focuses again on under-noticed aspects of domestic architecture, in this case, uneasy marriages of modest homes and outdoor vegetation.

What to grow and what to permit to grow evidently make unrelenting problems for many homeowners. Priola has titled his series "Nurture," apparently to indicate the opposite or flip side of nature, trouble spots where flora and human decisions, or indecision, collide.

Nurture: Grass (2014) shows a rumpled swatch of AstroTurf thrown over a bare patch between a garage and gated side entrance. The bit of surrogate lawn sits beneath a palm tree of seismic robustness seeming to menace the low stone wall containing it.

Nurture: Grey Wall (2014) finds a scrawny shrub apparently clinging desperately to a bit of trellis against a wall that appears to have been hastily painted in mismatched grays, perhaps to conceal graffiti.

Priola's new pictures, like many that have preceded them, remind us how many potential questions, how much intimate domestic history, may lie embedded on the margins of our attention. His interrogative gaze prepares visitors to Anglim for the much more searching attention demanded by the collages of Jean Conner, widow of Bruce Conner (1933-2008), whose work, stretching back decades, merits more notice than it has received to date.

SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

NOVEMBER 24th, 2011

Kimberly Chun, special to the Chronicle

Neighborhoods are all too easy to peg by their castoffs. For example, you might know certain segments of the Mission for their castoff mattresses or portions of South Berkeley for the fancy coffee left out by the curb.

Glen Park photographer John Priola, however, took a different tack when it came to capturing and cataloging the donations bundled up on the street for pickup by a favored nonprofit.

"I've participated in these nonprofit collections myself, putting out donations periodically," says Priola, 50, who will become the chair of the photography department at the San Francisco Art Institute in January. "But only in the last year have I started to pay attention."

What materialized is a series of 75 digital color images, "Philanthropy," which casts an eye toward the bags, boxes and bits of furniture that people put out for charity. Inextricably tied to those deliberately or loosely arranged trash bags and mystery objects are the homes they are leaving: stark stacks of apartments, hidden ranch houses, twisting Normandys, Marina-style row houses.

"Frankly, they're like still lifes to me, portraits of the people who put things out," the photographer says. "What drew me in was this underlying interest in stuff and how things are really representative of who we are as people. There's a real difference between the people who throw out trash on the street and people who set out belongings to be repurposed or donated. They're set out with care."

Priola asked friends to tell him when their neighborhoods were having pickups and shot in the morning in assorted neighborhoods and cities over the course of a year. For the first time, for this series, he moved from what he calls "an antiquated 4-by-5 black-and-white medium" to color and digital. "The subject mater really asked for it - or demanded it, actually," he says. "I wanted the present tense right there. I wanted it to be palpable, so it needed to be color and look like the world."

Nonetheless, "Philanthropy" connects to past work such as Priola's "Saved" series - which set the patched, glued and darned estate-sale discards and found objects against a rich, depthless black background - and the inadvertently poetic-sounding "Weep Holes," with its more architecture-centered images of those easy-to-miss drainage orifices. "There's two sides there - what's behind it and what's in front of it," the photographer says of the latter. "So much of my work is about what you can't see."

He didn't run into any poachers pawing through the street-side donations, but was once stopped by a donor who wanted to know what he was up to. "I was about to photograph his box of things and I told him I was photographing the generosity of the neighborhoods," Priola says. "I told him I could just skip it. And he said, 'Yeah, just skip it.'

"I don't blame him," he continues. "The people who donate still have attachment to the things."

In a related way Priola will add a social practice element to his work with this show: He asks visitors to bring toys, puzzles and gently used clothing to donate to Community Assistance for the Retarded and Handicapped, which is affiliated with Thrift Town. He'll photograph the collection as it grows.

"I always realized I can't just take advantage of someone else's attempts to make their community or organizations thrive," he says. "I didn't want to just piggyback and take."

SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2008

Kenneth Baker

J. John Priola shows a new series of black-and-white pictures at Gallery Paule Anglim that continue his survey of undernoticed details of domestic architecture.

This time he has turned his attention to vent grates in house foundations and the "weep holes" in retaining walls that permit drainage.

As in "Hillhurst Avenue" (2007), he offers these tiny architectural epiphanies, in a plainspoken manner, in big prints with wall, aperture, sidewalk and perhaps a fringe of vegetation forming a nearly depthless, nearly abstract pattern. A series of postcard-size prints examines single weeds obtruding, one or two at a time, between wall and sidewalk.

Priola poises these images on the border between documentary and conceptual art. They seem to equate the insufficient attention people give to details of the world and the insufficient attention they give to photographs. Such an equation would risk insulting the viewer, did Priola not effect it so discreetly that it too may pass unnoticed. Priola also quietly revives what Vancouver,sh Columbia, photographer Roy Arden calls "the romance of the index" - the excitement of believing, in the Photoshop age, that the phenomenon before the lens left its own photo-chemical imprint.

FEATURE: Reviews

J. John Priola

by Prajakti Jayavant

Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco

May 4 - May 28, 2005

Farm Sites and Other Works

J. John Priola’s exhibition “Farm Sites and Other Works” consists of gelatin-silver prints and a video projection. This series has been an ongoing project since 1999, recording Priola’s visits to farm sites in the U.S.A. Each work is photographed and printed by the artist himself. These decisions impact the enigmatic quality of Priola’s work.

At first glance, there doesn’t seem to be anything special about the places depicted in the series including Tower Road and Road 17. They don’t hold a prominent place on the map, nor are they noted historical sites. But soon, I am gracefully pulled in and wound around to experience scratching bark and feathered blades of grass. Fields raked as path draw me towards dilapidated trees and an immediate spatial lightness.

SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

SATURDAY, MAY 31, 2003

"Outside the window, a watcher in the dark"

Kenneth Baker

Does all photography have snooping as a subtext? All kinds of pictures support that idea, from images that capture things too fast, small or distant for the naked eye, to straightforward but stealthy ones such as J. John Priola’s series "Dwell" at Gallery Paule Anglim.

Each of Priola’s black and whites looks from deep blackness into the lighted window of someone’s residence. His titles identify locations but give no clue whether he collaborated with the people whose dwellings are captured. The faintly invasive feeling the pictures emanate suggest, correctly, that he did not.

The almost abstract formal elegance of Priola’s pictures offsets their creepy air of belonging to a stalker’s album. Yet their formality also reminds us of the time they involved and Priola’s risk of discovery in setting up his 4-by-5 camera.

"Dolores Street, Ground Floor South" (2001) reveals almost nothing of the domestic interior beyond. The nearly opaque curtain flattens the arched window into a tombstone shape. A hazy shadow pattern makes it hard to tell whether the view looks from outer blackness into a lighted window or out from a dark room at muffled light.

Priola’s pictures make a fascinating counterpoint to the "Summer Night" of Robert Adams at the Fraenkel Galley across the street.

New meanings: in J John Priola’s small, black and white photographs at Paul Kopeikin Gallery, such everyday objects as a wishbone, a pacifier and, a jewel box are imbued with menace, absurdity or melancholy. Some are spotlit as harshly as commercial products; others are silhouetted like antique portraits. All, however, are isolated within a darkened void, disengaged from any narrative, until we begin fabricating narratives for them. It's impossible not to do.

If these objects are conceived as clues, the context is cinematic---all white lights and portentous swells of music. If these are mnemonic devices, it is therapeutic, as a photograph of a syringe which seemed to insist. If these are pieces of evidence, the narrative context is juridical and matter-of-fact.

Indeed the only images that jar are those in which matter-of-fact-ness is eschewed for symbolism---such as an egg and an apple. These too easily devolve into hackneyed still-life studies, wherein classical beauty overwhelms the conceptual program.

The work as a whole is more ambitious. At the risk of staking a claim too grand for images so diminutive, one might argue that they function as allegories of the photographic project itself. Photography’s mandate is demonstrated as clearly as in any textbook.

Ordinary things are rendered extraordinary in and through the process of representation (cropping, framing, lighting, etc.). Meaning is conceived as an aftereffect, a residue of form.

In this case, form is so insistently sculptural it resonates with trickery. The objects seem to be winking at us. If trompe-l’oeil painting is uncanny by nature, these eccentric photographs redouble its effects. To become absorbed by their mundaneness is an unnerving experience.

Susan Kandel, special to the Times read article here.